King Richard III of England had two acknowledged illegitimate children. My last post considered the life of one, his daughter Katherine Plantagenet, Countess of Huntingdon. This time, we’re focusing on Richard’s illegitimate son, usually known as John of Gloucester.

As is the case with Katherine, we lack any clarity about John’s date of birth. Richard’s known illegitimate children are usually accepted to have been born before his marriage to Anne Neville, though this remains impossible to confirm. The identity of John’s mother also remains a mystery. He and Katherine may have shared a mother, or they could be two different women. Efforts to try to uncover John's mother have focussed on a lady named Alice Burgh.

On 1 March 1474, Richard made a grant of £20 a year, a very generous sum, to Alice whilst at Pontefract. The grant states only that it was made for ‘certain special causes and considerations’. There is one reference to John as ‘John de Pountfreit Bastard’ in Harleian Manuscript 433. Based on these two facts, it has been suggested that Alice Burgh might be the mother of John, who was the result of a relationship somewhere near to Pontefract. These are the frustratingly wobbly pillars on which so much of our understanding of Richard III is built.

The first occasion on which John becomes visible arises from the account of Sir George Buc, compiled in 1619 to tell the story of King Richard III. Buc’s account is, in many ways, the first effort to rescue and dust off the tarnished reputation of Richard III that had been trampled further into the dirt during the Tudor period that, for Buc, had recently ended. The most recent edition of Buc (a mammoth tome but one filled with interesting snippets) was edited by the late Arthur Kincaid, building on his previous work. It was published by the Society of Antiquaries in partnership with the Richard III Society. A digital edition of the book is now available for free, so if you have a few spare weeks, grab it and dive in! You can download it from https://library.oapen.org/handle/20.500.12657/94298

Buc notes that when Richard III went on his progress north, ‘the king graced many worthy gentlemen of the north parts with the title and order of knighthood’. In York, where his son and heir Edward of Middleham was formally invested as Prince of Wales, Buc also asserts, ‘as some say, [the king] made Richard of Gloucester, his base son, [knight]’. Join me in screaming at the use of the wrong name – what are you doing to us, Sir George!? We can be certain this refers to John rather than a Richard because Buc continues that this was the same illegitimate son who was ‘[after Captain of] Calais, who was a valiant young gentleman’. As the story progresses, it will become clear that John held the office of Captain of Calais, so we can be confident Buc has simply muddled his names up here. It’s also worth noting that Buc uses the get-out-of-jail-free phrase ‘as some say’ to let us know he isn’t certain this is a verified fact.

Similarly, there is a reference in the ordinances Richard established for the household of the Council of the North that may (or may not) include John. After the death of his heir, Edward of Middleham, Richard appointed his nephew, John de la Pole, Earl of Lincoln, as Lord President of the Council. The ordinances provide, amongst many other things, for the structure of meal times, including that ‘My lord of Lincoln and my lord Morley to be at one breakfast, the Children together at one breakfast’, and the rest of the Council at another.

Nowhere is it made clear who the ‘children’ were. We know that Richard’s nephew Edward, Earl of Warwick and his niece Elizabeth of York (the future wife of Henry VII) would arrive shortly after the ordinances were compiled. Was the provision in preparation for them? Was John already part of the household? It’s even been suggested that one or both of Edward IV’s sons (the Princes in the Tower) might have been there.

So far, so little we can actually see of John of Gloucester!

Our first reference to John in the chronology of his life is tricky. It uses the wrong name and is couched in uncertain terms, casting doubt on its validity. The other possible mention of him doesn’t actually mention him at all.

Fortunately, there are references to John from within his lifetime that can shed a little more light on his obscured story. There are also accompanying references that are open to more speculation. On 11 March 1485, John was appointed Captain of Calais, the role Buc mentioned that helped clear up the mistaken name of the knighted son of King Richard. The patent appointing John provided for him to exercise the authority of the Captain from a week earlier, on 4 March. In the text of the appointment, he is described as ‘our dear bastard son John of Gloucester’.

Elsewhere, in relation to the appointment, he is named ‘John de Pountfreit Bastard’ and is being made ‘Captain and lieutenant of Calais and the marches there and of our tower of Risebank of Guisnes and Hammes during his life’. It is this reference to him as John of Pountfreit – Pontefract – that has led to speculation about his place of birth and created the connection to Alice Burgh as a candidate to be his mother. No such supposition seems to emerge from references to him as John of Gloucester, which may well relate to his father’s title as Duke of Gloucester but equally may allude to his place of birth.

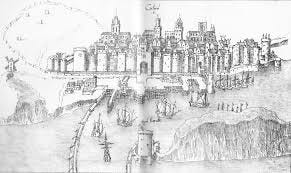

The office of Captain of Calais was a significant one, and its grant was a singular honour. Calais had been taken by the forces of Edward III in 1347, just after his victory at the Battle of Crecy. It would remain in English hands until 1558 when Mary I finally lost control of it. The Captaincy encompassed overall control of the town of Calais, the castles of Guisnes and Hammes, and the marches, the border around Calais that fell under English control. The boundaries of this authority were fluid and altered over time. It generally represented a wedge of English soil around 20 square miles in size that punctured French control like a thorn in the side of the crown in Paris. It had a thriving economy, and offered a bridgehead should any King of England decide to invade France. To the King of France, it was a constant, persistent, and embarrassing threat.

The grant of this office to John does not help us resolve the issue of his age. A Captain might, and frequently did, appoint a deputy to actually perform the role. If Buc is accurate in describing John as a ‘valiant young gentleman’ when he was knighted in 1483, and he was felt to be a viable candidate for the post of Captain of Calais in 1485, we might suspect that he was moving into his later teens by this point. That remains speculation, though. John might still have been much younger and was simply being positioned as a representative of his father’s authority after the loss of the king’s only legitimate heir.

It is clear that, whatever his son’s age, King Richard was looking to build something for John. Undoubtedly, that was to John’s benefit, and he was looking to be doing very well as a king’s illegitimate son, but the move also suited Richard. He was in a politically precarious position without a legitimate heir of his body. Faced with the growing threat from the exiled Henry Tudor, Richard needed to bolster his position and project a broad base of support. An illegitimate son could offer plenty of benefits there. Children born out of wedlock were considered incapable of acceding to the throne, as the fate of Edward V and his siblings in 1483 had clearly and recently demonstrated. John, therefore, could not claim his father’s crown but could reap the benefits of supporting it.

Alongside this, Richard was constructing an offensive alliance against France. Spain had offered a significant force if Richard would invade France. Richard was wooing the Duke of Brittany in an attempt to persuade him to join, and the Holy Roman Empire, then in control of Burgundy, was a potential ally, too. I suspect the reason that France eventually threw Henry Tudor across the Channel with their support and backing was to keep Richard occupied at home and prevent him from making a move to invade France. I doubt they expected Henry to succeed or cared about what might happen to him.

In this environment of both threat and aggression, John’s appointment becomes even more significant as his father’s representative in what would undoubtedly have been the landing place for an English army heading into France. Perhaps this even suggests that putting a child there was unlikely and that John was old enough to be considered able to act in this capacity for his father.

Around this appointment, there is also a reference that is less clear and has been the subject of some speculation. Speculation, I would add, that I have engaged in.

On 9 March, just before John’s appointment, Henry Davy was instructed to deliver to ‘John Goddeslande footman unto the Lord Bastard two doublets of silk, one jacket of silk, one gown of cloth, two shirts and two bonnets’. So far, we have seen John described as ‘John de Pountfreit Bastard’, and ‘our dear bastard son John of Gloucester’. It is not unreasonable, particularly in the context of his appointment as Captain of Calais, to assume the reference to ‘the Lord Bastard’ is to John. However, nowhere is he described in an explicit reference as a lord. It may be that, as a son of a king, illegitimate or not, John was considered by his contemporaries, at least informally, to warrant the use of the title ‘lord’. He is not the only candidate for a person to whom this might refer, though.

The Princes in the Tower are widely assumed to be dead by this point. I’ve used the word assumed a couple of times now, and I’ve done so deliberately. Assumptions are dangerous, and although some sneer at questioning the fate of Edward IV’s sons and this reference, interrogating the evidence we have with an open mind is essential.

The Wardrobe Accounts in 1484, in reference to Richard III’s coronation the previous year, refer to material purchased for Edward V. The intention appears to have been for Edward to attend his uncle’s coronation. In the Wardrobe Accounts, Edward is referred to as ‘Lord Edward, son of the late Kyng Edward the Fourth’. So, there was a bastard in England in 1483 who was considered a lord. By extension, Edward’s younger brother Richard, Duke of York might also have been called a lord. Could a reference to the Lord Bastard mean one of the Princes in the Tower? Clothes had been purchased for Lord Edward in 1483. Why not again in 1485? Unless you’re adamant they were dead, something of which you cannot be certain, it is possible.

Earlier than this, on 18 July 1483, a warrant was issued for the payment of fourteen men who had provided service to Edward IV and ‘Edward Bastard late called King Edward the Vth’.

There is another reference to a Lord Bastard. In November 1484, payments were made for ‘leavened bread allowed for the Lord Bastard riding to Calais 12d, and paid for a pike given to Master Brackenbury Constable of the Tower who at that time returned from Calais from the Lord Bastard 3s 4d’. These payment, referring again to a Lord Bastard travelling across the Channel, have been assumed to relate to John, though if made in November 1484, it came four months before his appointment. Had Brackenbury delivered the younger of the Princes in the Tower to safety on the continent? Perhaps. Perhaps not.

This is all that is known of John during his father’s life. It isn’t much, is it? Later accounts refer to ‘money paid to the said late King Richard and John of Gloucester his son Captain of the said town and the soldiers of the same’. Here, he is John of Gloucester again, not Lord Bastard. Henry VII made a payment on 1 March 1486 to ‘John de Gloucester, bastard, of an annual rent of 20l. during the King’s pleasure’. The new king appears to have felt he had nothing to fear from a recognised illegitimate child of his predecessor, though John was replaced as Captain of Calais by Giles Daubeney, a close associate of Henry.

John vanishes once more after this. Did he take part in the 1487 rebellion against Henry VII, which is remembered as the Lambert Simnel Affair? Was he at the Battle of Stoke, seeking to restore his own fortunes by championing a return to Yorkist rule? A herald’s account of the battle noted that ‘‘there was taken the Lad that his Rebels called King Edward, whose name was indeed John, by a Valient – and a gentle Esquire of the King’s House, called Robert Bellingham.’ John de la Pole, Earl of Lincoln was killed at Stoke. The only significant John who might have been taken alive is John of Gloucester. Did a herald mistake Richard III’s illegitimate son for the leader of the army? If so, it would explain our next mention of John.

By 5 October 1497, the second claimant to Henry VII’s throne, who had claimed for half a dozen years by this point to be Richard, Duke of York, younger of the Princes in the Tower, was in custody. This man is remembered by history by another name: Perkin Warbeck. He subsequently signed a confession (I suspect this was written for him, and he was beaten until he put his name to it, but that’s another story). As part of the confession that he was really Perkin, a boatman’s son from Tournai, the detail was included that ‘King Richard’s bastard son was in the hands of the King of England’.

John was a prisoner. This is the last contemporary reference to Richard III’s illegitimate son. The only other comment on his fate is found in Sir George Buc’s account, written in the early seventeenth century. Compiled from numerous manuscript sources that have not survived, Buc asserts that John was executed in 1499 alongside ‘Perkin Warbeck’ and Edward, Earl of Warwick. Buc wrote that at the time of those two executions, ‘It happened about the same time that these unhappy gentlemen [su]ffered there was a base son of King Richard III [ma]de away, and secretly, having been kept long before [in] prison.’

He claims that this was Henry VII’s response to rumblings in Ireland that aimed to make John king. That seems unlikely and was perhaps little more than a weak excuse to be rid of John along with the other two Yorkist figures. Henry was sweeping his kingdom clean, and if Buc is to be believed, John was sacrificed to achieve that end.

That is all that we know of John. In common with his (half?) sister Katherine, he is hard to discern clearly. He bursts to the fore briefly and fades into uncertainty and mystery every bit as quickly. The only end we have suggested for him with any confidence is that he was kept as a prisoner by Henry VII for a number of years and then executed. When the fate of Edward, Earl of Warwick, and of ‘Perkin’, who might have been the real Richard, Duke of York, we should add John to the list of young men sacrificed at the altar of Tudor security.

The only question now is whether Richard had any other illegitimate children. That’s a story for next time.

What evidence does Buc have for John of Gloucester being executed or is it mere speculation?