Although Richard III acknowledged two illegitimate children, Katherine Plantagenet and John of Gloucester, rumours have persisted that he had other children too. In two previous posts, I have considered what we know about Katherine and John, so let’s have a look at these mysterious others.

The best known of these candidates to be a child of Richard III is a man known as Richard of Eastwell. His story is an odd one, and it hinges around an entry in the records of Eastwell Church in Kent. On 22 December 1550 is the record of the death of a man named Richard Plantagenet appears in the parish records. Who is this man who used the name of a royal house deposed 65 years earlier?

Fortunately, we have some clues about what was going on. The story comes from a letter penned in 1733 by a Dr Brett to his friend William Warren, the President of Trinity Hall, Cambridge. Dr Brett was relating a story he had been told by the Earl of Winchelsea. It was an intriguing tale of a bricklayer who claimed royal descent.

Here is the text of the letter:

When Sir Thomas Moyle built that house (that is Eastwell Place) he observed his chief bricklayer, whenever he left off work, retired with a book. Sir Thomas had a curiosity to know, what book the man read; but it was some time before he could discover it: he still putting the book up if any one came toward him. However, at last, Sir Thomas surprized he snatched the book from him; & looking into it, found it to be in Latin. Hereupon he examined him, & finding he pretty well understood that language, he enquired, how he came by his learning? Hereupon the man told him, as he had been a master to him, he would venture to trust him with that he had never before revealed to any one.

He then informed him that he was boarded with a Latin schoolmaster, without knowing who his parents were, ‘till he was fifteen or sixteen years old; only a gentleman (who took occasion to acquaint him he was no relation to him) came once a quarter, & paid for his board, and took care to see that he wanted nothing. And one day, this gentleman took him & carried him to a fine, great house, where he passed through several stately rooms, in one of which he left him, bidding him stay there. Then a man finely drest, with a star and garter, came to him; asked him some questions; talked kindly to him; & gave him some money. Then the ‘forementioned gentleman returned, and conducted him back to his school.

Some time after the same gentleman came to him again, with a horse & proper accoutrements, & told him, he must make a journey with him into the country. They went into Leicestershire, & came to Bosworth Field; & he was carried to K. Richard Ill. tent. The King embraced him, & told him he was his son. But, child, says he, tomorrow I must fight for my crown. And, assure your self, if I lose that, I will lose my life too: but I hope to preserve both. Do you stand in such a place (directing him to a particular place) where you may see the battle, out of danger. And, when I have gained the victory, come to me; I will then own you to be mine, & take care of you. But, if I should be so unfortunate to lose the battel, then shift as well as you can, & take care to let nobody know that I am your father; for no mercy will be shewed to any one so [nearly] related to me. Then the king gave him a purse of gold, & dismissed him.

He followed the king’s directions. And, when he saw the battel was lost & the king killed, he hasted to London; sold his horse, & his fine cloaths; &, the better to conceal himself from all suspicion of being son to a king, & that he might have means to live by his honest labour, he put himself apprentice to a bricklayer. But, having a competent skill in the Latin tongue, he was unwilling to lose it; and having an inclination also to reading, & no delight in the conversation of those he was obliged to work with, he generally spent all the time he had to spare in reading by himself.

Sir Thomas said, you are now old, and almost past your labour; I will give you the running of my kitchen as long as you live. He answered, Sir, you have a numerous family; I have been used to live retired; give me leave to build a house of one room for myself in such a field, & there, with your good leave, I will live & die: and, if you have any work I can do for you, I shall be ready to serve you. Sir Thomas granted his request, he built his house, and there continued to his death.

Sir Thomas Moyle was captivated by the astounding tale of the bricklayer. Seeing the old man sitting apart from everyone else during his breaks, looking through a book, Sir Thomas tried to catch him out. When he finally crept up on the man and caught him with his book open, he was bemused to find it was a Latin tome. This only intrigued Sir Thomas further. Refusing to believe the man could read Latin, Sir Thomas quizzed him, only to discover he could indeed understand the book. Now, Sir Thomas demanded to know the man’s story.

This is the tale above. The man claimed his name was Richard Plantagenet. He had never known who his parents were, but his education had been paid for. Suddenly, he had been taken from his school to Bosworth in Leicestershire and thrust into the tent of King Richard III as he prepared for the impending battle. He was told that he was Richard’s illegitimate son, and that he would be recognised as such if the king was victorious, but warned to disappear if the battle went badly.

When Richard lost Bosworth, the lad made his way to London, sold his horse and fine clothes, and became a bricklayer. In his older years, he’d come into Sir Thomas Moyles’ to work on the rebuilding of Eastwell Place. Sir Thomas was clearly impressed and allowed the man to build a house on his land where he lived out the rest of his days, until his death, noted against the name Richard Plantagenet on 22 December 1550.

It seems that this Richard Plantagenet, the aging bricklayer who read Latin and claimed to be the illegitimate son of Richard III, became a dinner table novelty for the Moyles family and the story was still being retold almost 200 years later.

There was a ruined cottage on the land around Eastwell Place that was called Plantagenet Cottage. The current building there is a newer one. There is a table tomb at Eastwell Church that has traditionally been identified as the resting place of Richard Plantagenet, though it is now believed to belong to a member of the Moyle family. Nevertheless, the man identified in the parish records as Richard Plantagenet is buried somewhere there.

So, was this man an illegitimate son of Richard III? There’s no real way to verify the Moyle family story of his life. It would seem odd for Richard to acknowledge and provide for two children, but not another. However, it is worth noting that Katherine and John both only come to the fore during Richard’s reign. Both were positioned in ways that suggest they were old enough to be politically helpful to their father. Katherine was married to an ally, and John was to represent Richard in Calais. The position of this Richard of Eastwell as a schoolboy suggests he was younger, which has two significant impacts.

Firstly, he was not old enough to be active in his father’s regime, which might explain why he had not been brought to prominence yet. Neither Katherine nor John make an appearance until they are taking a role in their father’s government. If this Richard was an illegitimate son, then he might not have been old enough to take such a step yet, and therefore to be recognised publicly by his father. If his story is true, it is clear his education was being paid for and he was well provided for nevertheless.

The second impact of his potential age is that he would have been the result of a liaison during Richard’s marriage to Anne Neville. Katherine and John are believed to have been born before the marriage, so there would be no stain of unfaithfulness. If Richard of Eastwell was a schoolboy in 1485, he would almost certainly have been born after the marriage (which took place around 1471/2). It remains possible he was born just before the marriage, and was at the end of his schooling, particularly since he was tasked with heading off to London alone to make a life for himself. If there was a further reason he was kept secret and not recognised publicly by his father, it might have been the infidelity he would have represented.

Putting his birth between, say 1470 and 1475, he would have been 75-80 at his death in 1550. That is not beyond the realms of possibility.

So, who was this bricklayer? We know who he claimed to be, but there is no evidence to support his claim. Was he an illegitimate son of Richard III, provided for in his youth and waiting to be of an age to be recognised by his father? Or was he a bricklayer, who might have picked up a little Latin, and sold a sparkling story to an employer. After all, he did get a free house to live in for the rest of his life, and the status of a minor celebrity that has persisted for almost 500 years since his death recorded him as Richard Plantagenet of Eastwell.

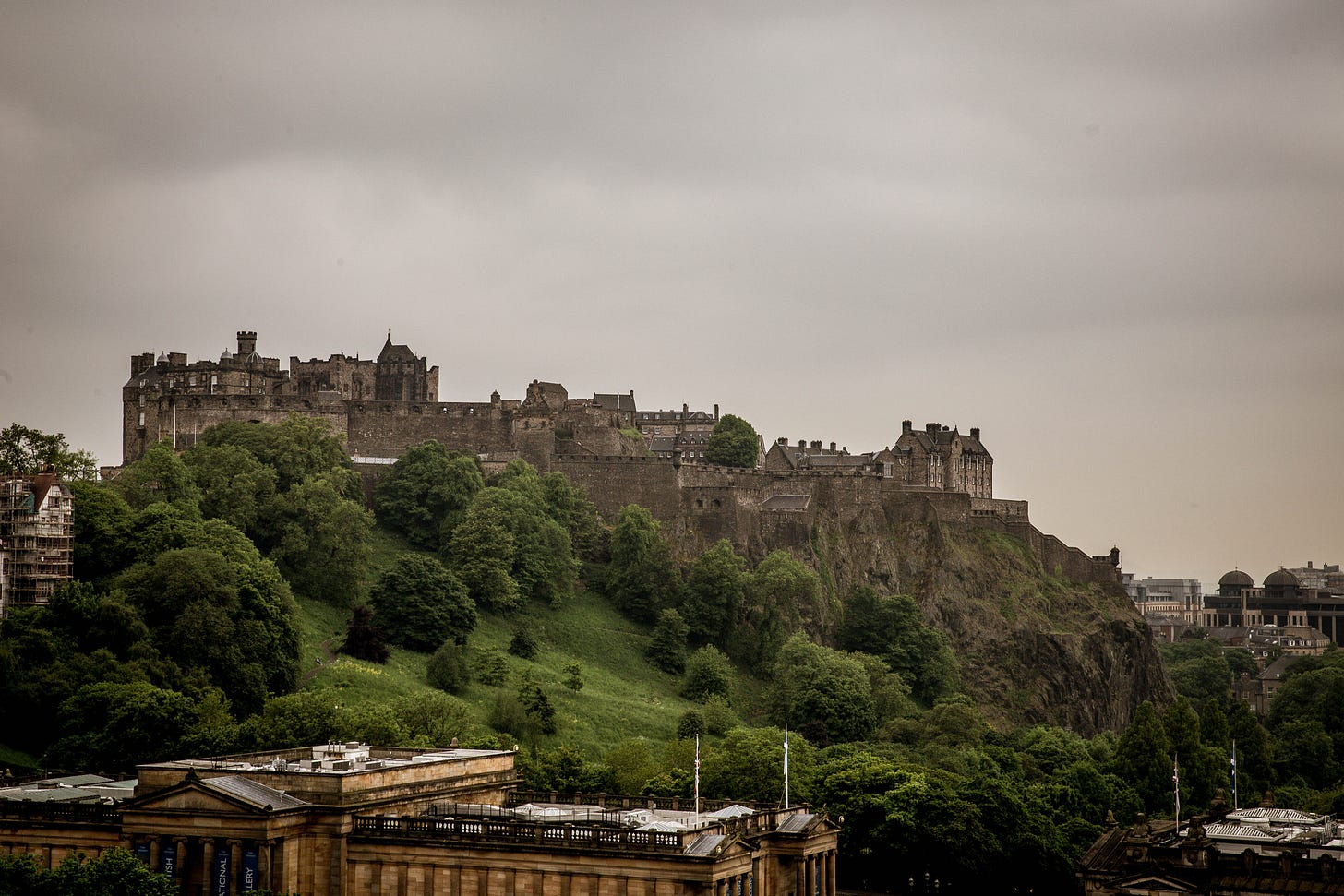

There is one mother person who has been suggested as a speculative illegitimate child of Richard III. There is less evidence of this than for Richard of Eastwell, but nevertheless, Anne Hopper is claimed by a family tradition to have been the result of a relationship between Richard, as Duke of Gloucester, and a lady from Edinburgh.

This story first appears to be recorded as part of an obituary for an architect, Thomas Hoper, when he died in 1856. It reads:

This eminent architect, who died on the 11th of August, at Baywater Hill, was born at Rochester, in Kent, July the 6th, 1775, and was in the eighty-first year of his age. There exists a most curious tradition in his family that they are descended from a natural daughter of Richard by a lady the king brought with him from Edinburgh to Dover. This daughter married a wealthy yeoman possessing property near Canterbury and to this day there is a farm, a mill, and a field bearing the family name of Hopper, but now no longer in their possession.

The obituary goes on to recite briefly the story of Richard of Eastwell too, presenting it as truth. Presumably, this is the hopes of supporting the story of Anne Hopper. The story is repeated in connection with a ring the purports to contain a piece of the True Cross that was displayed at a museum in Eyam in Derbyshire. Part of the text alongside the ring stated:

The ring was given by King Richard III to Anne Hopper, ancestress of Thomas Hopper, the architect and is mentioned in some of the obituary notices of the last named. It passed to Thomas Hopper’s youngest daughter, Jessaline, wife of Sir Benjamin Smith of the Corps of Gentlemen at Arms to Queen Victoria and thence to her only child Emily Euphemia, wife of Henry Osbourne White. According to Lady Smith documents relating to the Hopper affair, including a promise of enoblement of Anne Hopper’s children by Richard III, were burnt by Thomas Hopper’s father in a fit of drunken spleen.

How convenient that the proof was burned in a ‘drunken spleen’! I must try that next time the tax man comes knocking.

The story of Richard of Eastwell is certainly an intriguing one. The claim that Anne Hopper was another illegitimate child of. Richard III seems, from the obituary of Thomas Hopper, to rely on the truth of Richard of Eastwell’s story as the scaffolding to support the Hopper family legend.

For me, there is not enough to offer any confidence that either Richard of Eastwell or Anne Hopper were previously unknown illegitimate children of King Richard III. There are possible reasons, most notably their ages, why they might not have been publicly recognised by Richard. Katherine and John only emerge as his accepted children when they are old enough to be of service to his struggling regime and dynasty. But I don’t buy either of them. I would suggest Richard of Eastwell span a story that earned him a house, and that the Hopper family perhaps developed a legend of a royal origin that might have been intended to boost their societal credentials.

So, I think, we are left with two illegitimate children of King Richard III. Katherine and John were born of unknown mothers and only become prominent once their father is king. He clearly intended to offer them prominent roles in his regime, even before the loss of his only legitimate son and heir.

This is striking. Richard’s brother Edward IV had several illegitimate children but did not recognise them or put them to any use in his government. In a Yorkist context, it is therefore unusual. Other monarchs in England and rulers on the Continent were content to employ illegitimate children, not least because they posed no threat to the crown they were connected to. Philip the Good, Duke of Burgundy had an illegitimate son named Anthony, known as the Bastard of Burgundy, who was one of the most famous tournament knights in Europe, fighting in England in 1467 whilst Edward was king. Richard also spent two periods of exile in Burgundian territory, so had the opportunity to view and consider how illegitimate children could be brought into a regime.

What do you think? How many illegitimate children do you think Richard III had? Have you heard of any I’ve not mentioned?

The story of Richard of Eastwell is even more fascinating than those of Richard's other 2 illegitimate children. It's fascinating because it's his own story. It doesn't mean it's true but it's a possibility. Richard may not even have been aware of the lad until just before Bosworth. It seems it would be strange to tell someone they are your son, if they're not. Remember the only actual way to establish fatherhood was for them to acknowledge you. It didn't matter what you claimed or believed unless the father claimed you as his own. If you were married, then of course it was assumed you were the father of your wife's children, unless you denounced them. Illegitimate children couldn't inherit but could be granted a title, an allowance and position. Richard clearly couldn't give this son anything as he was too young or recently came to light. I don't know if he was Richard iii's son, perhaps we might never know, but his story is remarkable. If he was Richard's son, he was afforded an education. We can only wish it to be so. One question, are there any bones in that tomb? It looks like an odd place for a real tomb.

I find this thread very interesting. The fact that Richard III acknowledged two illegitimate children seems to indicate he would have no problem acknowledging a third. On the other hand events were moving quickly towards Bosworth and therefore he had pressing matters on his mind. In the end I do find it hard to believe a man as honorable as Richard would fail to provide for one of his children, legitimate or illegitimate.