Richard III and his wife, Queen Anne, had only one recorded child. Whether they suffered the loss of any other child is not recorded. When this son, Edward of Middleham, Prince of Wales, died in the Spring of 1484, aged around 8 (his date of birth is not known with any certainty and is sometimes given as being as early as 1473), it created a political as well as profoundly personal crisis for the royal couple.

Illegitimate children were by no means uncommon among royalty and nobility during this period. Edward IV had at least five illegitimate children, though none were acknowledged during his lifetime. Richard Neville, Earl of Warwick had an illegitimate daughter for whom he did provide. There were a number of different attitudes to illegitimate children that might be adopted. They might be very useful. They were in a position to offer loyalty, but their birth barred them from succession, particularly to the crown and, increasingly by the 15th century, to noble titles, too. They may provide valuable support without representing a threat. Sounds ideal.

Against this, some might perceive a danger in building up illegitimate children and creating expectations that they could never see realised. The reward for their valuable support might always seem limited. This would risk creating in them a sense of feeling hard done by that could see them turn whatever authority, wealth, and/or military power they had accumulated against their father (usually).

The Bastard of Fauconberg was an illegitimate son of William Neville, who became Earl of Kent at the accession of Edward IV. William was an uncle of Richard Neville, Earl of Warwick and an experienced soldier. The Fauconberg title belonged to William in right of his wife Joan de Fauconberg, yet this was the title William used when his illegitimate son Thomas began to rise to prominence. Thomas became closely associated with his cousin Warwick and shared the earl’s naval expertise. When Warwick fell at the Battle of Barnet in 1471, Thomas commanded the Neville fleet and landed in England to lay siege to London for a time. Here was a salutary lesson in the dangers of creating powerful forces of illegitimate children.

As with so many other things, there was a balance to be found, not least of which might require them to reach a level of maturity so that their personality and temperament might be weighed into any decision about what, if anything, to do with them.

The death of Edward of Middleham left Richard III without a legitimate heir of his body to succeed him. The rebellions of October 1483 had exposed fissures in his support in the south-east of England. Any king would struggle with becoming suddenly so dynastically insecure, but Richard had other issues that made it even more problematic for him. Not least of these was Henry Tudor, who was gathering to him those alienated from Richard’s rule into what looked like an increasingly serious threat.

This moment of crisis in the Spring of 1484 was not the catalyst for Richard III turning some focus on his illegitimate children, though it may have drawn their position as potential pillars of support into sharper relief. Richard acknowledged two young people, a boy and a girl, as his illegitimate children. We’ll come to the question of whether there were any more shortly. He had been happy to recognise and provide for them before the death of Edward of Middleham, suggesting that he felt some responsibility for them as his natural children.

Frustratingly, little is known about those two youngsters. They are John and Katherine, the acknowledged illegitimate children of King Richard III. Neither's age is known with certainty, nor are they easy to establish. John is usually presented first as if he were the elder, but no real evidence supports that supposition. I will return to him and those elusive others in a later post.

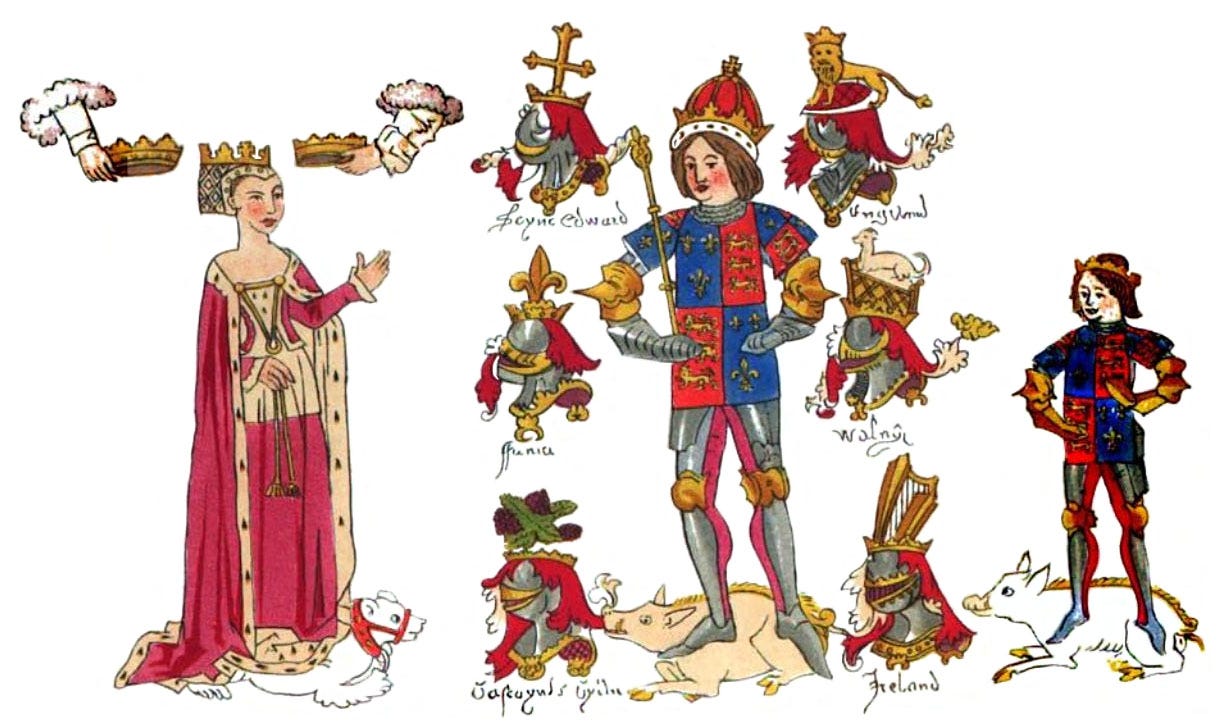

Katherine is the only known daughter of Richard III. She leaps to prominence in the early weeks of 1484, before the passing of her half-brother Edward of Middleham. On 29 February 1484, a document was created in which William Herbert, Earl of Huntingdon ‘promiseth and graunteth to our said souverain lord that before the feast of St Michael next commying by God’s grace he shall take to wiff Dame Katerine Plantagenet, daughter to our saide souverain lord’.

William signed a marriage agreement, covenanting that he would marry Richard III’s daughter Dame Katherine Plantagenet by 29 September 1484 – ‘the feast of St Michael next commying’ being Michaelmas. The earl was to provide Katherine with a jointure worth £200 a year. This meant Katherine would receive lands to this value from William’s estates, which she would hold for the rest of her life. In return, the king would pay for the entire cost of the wedding and provide the couple with an income of 1,000 marks (£666) per annum. This was to be made up of 600 marks from lands held by the king and 400 marks of land they would receive on the death of Thomas, Lord Stanley.

This last provision is interesting. While Lord Stanley lived, the 400 marks would be made up from estates recently taken from the Duke of Buckingham, who had been executed in November 1483 for his part in the rebellions of the previous month. The lands due to Katherine and William on Lord Stanley’s death were those he had received due to the guilt of his wife, Lady Margaret Beaufort, in those same October Rebellions. Richard was parcelling out the Beaufort inheritance while Lady Margaret was still alive to be enraged. It was a measure that might have caused her to redouble her efforts to depose Richard and, by now, replace him with her son, Henry Tudor.

Katherine is a figure who remains elusive even at the centre of her own marriage negotiations. We have no evidence to help us discern when she was born. It is generally accepted that both Katherine and John were born of relationships Richard engaged in before his marriage to Anne Neville. The date of that marriage is – surprise, surprise! – unknown. It may have been as early as 1472 or as late as 1474. I tend to favour an earlier date, which would place Katherin’s date of birth somewhere between, say, 1466, when Richard was 14, and 1472 when he married. It might be later; we simply can’t be sure. So, in February 1484, Katherine would probably be between 12 and 18 years old. The fact she was marrying an earl who was perhaps in his early 30s doesn’t help us since such age gaps were not unusual.

There is no evidence to tell us who Katherine’s mother was. She may have shared a mother with John, though it seems more likely that they had different mothers. There have been efforts to try to identify potential mothers. In Katherine’s case, one lady who is frequently suggested is Katherine Haute. The two share a name, and it is not one that was common amongst the York family of the king. In 1477, Katherine Haute was given an annuity of £5 a year by Richard (then Duke of Gloucester). There is no reason given for the generous gift, which means it might relate to an illegitimate child or it might not.

In March 1484, just after the marriage agreement was made, Richard ordered the Royal Wardrobe to purchase large amounts of rich materials, which appear to have been for the wedding he was funding. The instruction states the cloth of gold, velvet, satin, and damask was for the ‘lord of Warwick, the lady his sister, the lady Katherine, the lord of Huntingdon and other ladies and gentlemen’.

This union was undoubtedly beneficial for Richard. His legitimate son was still alive in February 1484 when the agreement was made, but his marriage would have most likely been meant for the greatest possible international diplomatic benefit. William Herbert’s father, also named William, had been Earl of Pembroke. He was known as Edward IV’s master-lock in Wales because of the control he held there for the first Yorkist king. William Senior was made Earl of Pembroke in place of Jasper Tudor to reinforce his position, but this brought him into conflict with the Earl of Warwick. When Warwick rebelled against Edward in 1469, Herbert was a casualty of Warwick’s ruthless retribution.

In 1479, William Junior was required to surrender the earldom of Pembroke to Edward IV, who was attempting to build up his son’s presence in Wales. Herbert was made Earl of Huntingdon by way of compensation. Richard had spent some time during the growing breach between Edward IV and Warwick with Herbert around the Welsh borders. The two appear to have become fast friends, and this match was perhaps meant to formalise that friendship but also to sure up Richard’s connections to the Marches and further into Wales. It cannot be a coincidence that at Henry Tudor’s side was his uncle Jasper, who still claimed the title Earl of Pembroke. Richard now needed his master-lock in Wales and might have hoped William Herbert Junior would fit the bill.

In line with what is now a common theme, no date of the marriage of Katherine and William is recorded. It was due to be completed before 29 September 1484 but may well have taken place in late May. On 27 May, Richard granted William formal recognition of his title as Earl of Huntingdon (his experiences may have made him wary of losing it), which may have been a result of the completion of the marriage contract. During that month, Richard also granted lands confiscated from rebels to ‘William Erle of Huntingdon and Kateryn his wif’.

In March 1485, Richard gave a further annuity of £152 10s 10d from lands he held in Wales to Katherine and William until they received the lands they were due. Little else is known about the couple’s relationship. No children are recorded being born to them, and William’s heir would be his daughter by his first marriage (to Mary Woodville, a sister of Queen Elizabeth Woodville), Elizabeth Herbert.

At the coronation of Elizabeth of York on 25 November 1487, William Herbert is listed amongst earls in attendance who were described as widowers. If this was the case (there is some doubt about the accuracy of at least one other description of an earl as a widower), then Katherine was already dead, probably still in her teens. A recent discovery by Dr Christian Steer has revealed Katherine’s burial place, which had been lost. Amongst records of church monuments, Dr Steer discovered an entry for Katherine as Countess of Huntingdon, suggesting that she had not been set aside by her husband when Henry Tudor came to the throne, at the church of St James Garlickhythe in London.

The church was destroyed during the Great Fire of London in 1666. It may be that the Herbert family had a London home at Worcester House, which was linked later to the family. This lay in the parish of St James Garlickhythe, so it seems possible Katherine died there and was buried in the local parish church, significantly as Countess of Huntingdon. Perhaps she fell victim to the sweating sickness that swept through London, brought by Tudor’s invading army.

William Herbert died on 16 July 1491. He was buried at Tintern Abbey alongside his first wife, the mother of his heir, as he had requested in a will dated 1483. This is more likely to reflect the lack of children from his match with Katherine than any lack of feeling for her or even shame at her parentage that the new Tudor regime might have caused.

Katherine Plantagenet remains an elusive figure. We know only a few facts about her, mostly surrounding her marriage, and none of them allow us to feel like we get to know her at all. It may have been some comfort to her that her father, unlike his brother, was happy to recognise his illegitimate children and make provision for them. In Katherine’s case, marriage to an earl might have been more than she had hoped for. Undoubtedly, the match served Richard III’s political needs rather than being a love match facilitated by a loving father, but that doesn’t preclude Richard from caring for his daughter, too. At the very least, we know she was buried with some care, as a countess.

What about Richard’s other illegitimate child(ren)? Well, that’s a story for next time.