On Sunday, 17 November 2024, a decade-long project to recreate as accurately as possible the voice of a fifteenth-century King of England revealed the fruits of its work. The Voice for Richard Project, led by voice coach Yvonne Morley-Chisholm, has brought together history, science, art, and technology, assembling a team of leading experts to produce a digital avatar of Richard III that moves and speaks, with the voice of actor Thomas Dennis.

I hardly need an excuse to be interested in a project involving Richard III. When Yvonne asked me for a bit of advice, particularly in finding documents that got as close as possible to Richard’s own words rather than a scribe writing formal, formulaic language, I didn’t hesitate. Alongside that, History Hit hopped on board to create a documentary that followed the project to its grand reveal - keep reading to find the trailer. You can subscribe to History Hit to get access to fantastic documentaries and ad-free podcasts.

I can offer some context to the project, which has hit the news in the last few days, but first, here’s what happened at the launch event. It was a fascinating experience, and being in York on Sunday was to indulge in an electric atmosphere of excitement. The only downside for the audience was having to sit through a talk I gave.

Playwright Bridget Foreman deconstructed Shakespeare’s Richard III to show that in the Scrivener’s scene, which is often omitted from productions, exposes the lie in the Bard’s drama. Next, I considered the people Richard spent his time with throughout his life. Experts assert that the people around us influence our accent and language, so who was Richard hearing and how might that have affected him? Most of them were northern, specifically focussed on Yorkshire, so despite his East Midlands birth, a northern influence is likely.

The final talk of the first session came from Philippa Langley, who explored the contemporary accounts of Richard III’s character and personality. Those who met him, even when writing for a foreign audience beyond Richard’s reach, were effusive in their praise of him. Niclas von Popplau stands out as a commentator who compiled his travel diary following time spent in Richard’s company and found him a worthy prince.

After lunch, Professor Caroline Wilkinson explained the process and development of facial reconstruction. I was intrigued to hear about the ‘Uncanny Valley’. I’d never come across it before, but it results from the measurement of people’s reactions to robots and digital recreations of humans. There is a point between unrealistic representations of human faces and the kind of hyperrealism that is increasingly possible today in which the face is nearly human but not quite right. That point creates a reaction akin to revulsion in an audience – acceptance of the image dips away before recovering as it becomes hyper-realistic.

Professor David Crystal next broke down the linguistics behind the pronunciation the project employed. OP – Original Pronunciation – is the art of recovering the way words were said in the past. Just after Chaucer wrote in Old English that we would find almost impossible to understand, the Great Vowel Shift began, drastically altering pronunciation very quickly so that by the time Richard III was speaking, a modern audience would be able to follow his meaning, even if some words would still sound a bit odd. David explained that before the widespread use of the printing press, phonetic, non-standard spelling is a great guide to pronunciation.

The final talk was given, fittingly, by the project’s lead, Yvonne Morley-Chisholm, who explained the birth of the project. Yvonne had been asked to give a keynote address during a conference in Leicester, and the most obvious thing to talk about in Leicester was Richard III. The idea of recreating a voice from the late fifteenth century grasped Yvonne and only grew when she saw an early attempt to animate a facial reconstruction. From there, Yvonne assembled an Avengers-style group of leading professionals to define, refine, and progress the project to give Richard III his voice back.

Yvonne then introduced Thomas Dennis, the actor who provided the voice and facial movements that brought the digital avatar to life. Thomas is a rising star, currently on stage in Stoke-on-Trent as Aramis in a production of The Three Musketeers. He has a YouTube channel, Swipin Thru History, and has long been interested in the Wars of the Roses. He also portrays Richard III in Warwick Castle’s Wars of the Roses re-enactment displays. Thomas put in a huge amount of work with Yvonne and David Crystal to get his pronunciation as close as possible to what Richard’s would have sounded like and build emotion into the performance.

The passage that was then shown to an eager audience was from an address to the archbishops and bishops on the investiture of Richard’s son as Prince of Wales. It’s based on a letter written at Nottingham. The original was in Latin, but in seeking words Richard would have employed in his lifetime, this passage was interesting because we see him as the proud father, looking toward a bright future for himself and his son. It’s a view unmarred by knowledge of the tragedies to come. Given that it’s a letter originally in Latin, we can’t be certain Richard ever spoke these words in English. It’s not unlikely that he created the words in English to be crafted into their written Latin form, so he may have spoken them to a scribe. The issues around whether the words were ever spoken were outweighed by the personal nature of the subject and the connection it offered to Richard’s family. In addition, it’s a poetic and creative address.

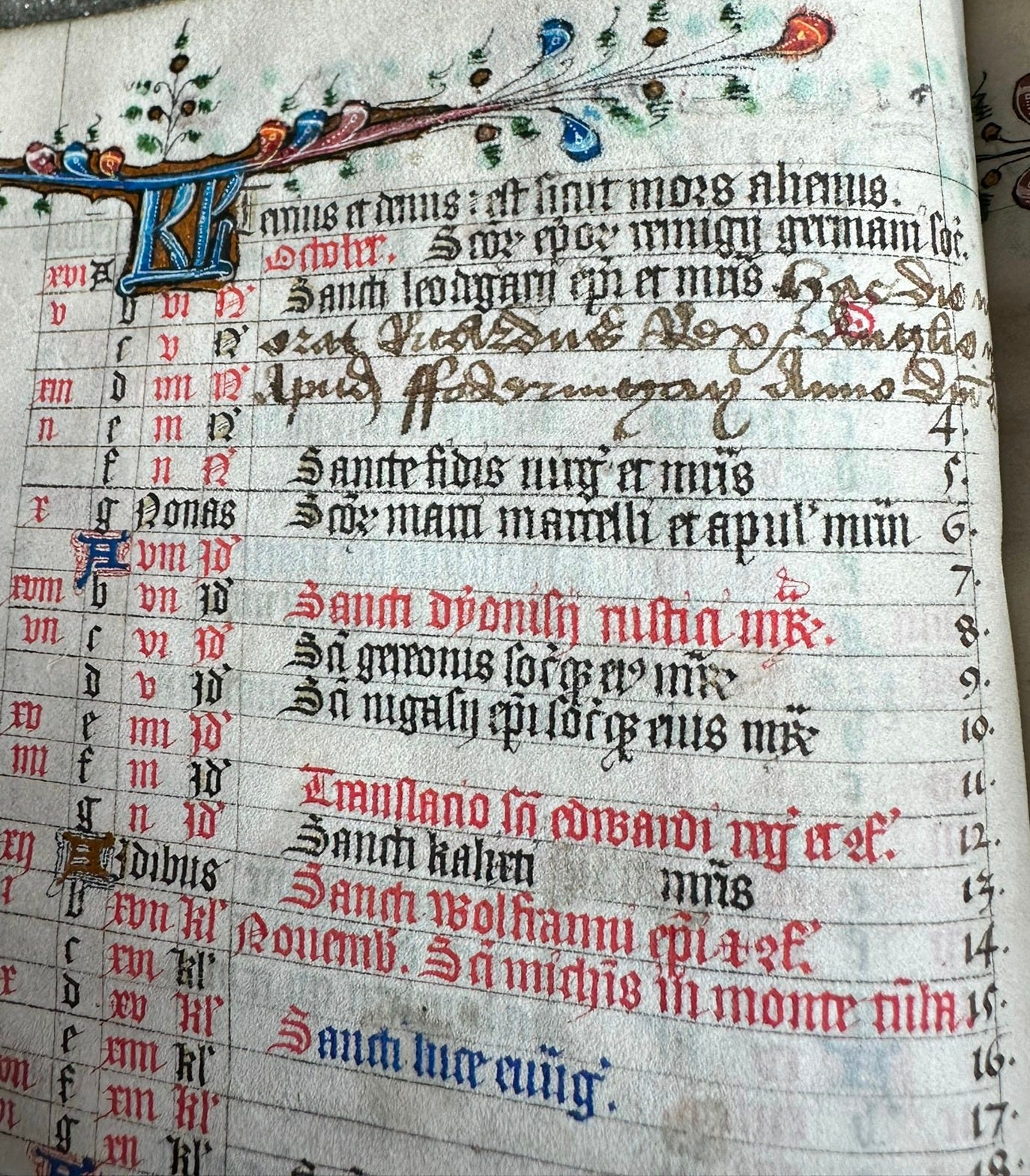

There are two more passages that will be recreated next year – each short animation takes a huge amount of time to build and perfect. One of the two pieces to come is similarly translated from Latin. It is part of Richard’s personal prayer, found within his Book of Hours, a precious and beautiful thing that passed after Bosworth into the hands of Lady Margaret Beaufort. As part of the documentary process, I got to visit Lambeth Palace Library to see the Book of Hours. It really is a beautiful object with some stunning illuminations. In the calendar section, on 2 October, is an entry that records that date as the birthday of King Richard, born at Fotheringhay in 1452.

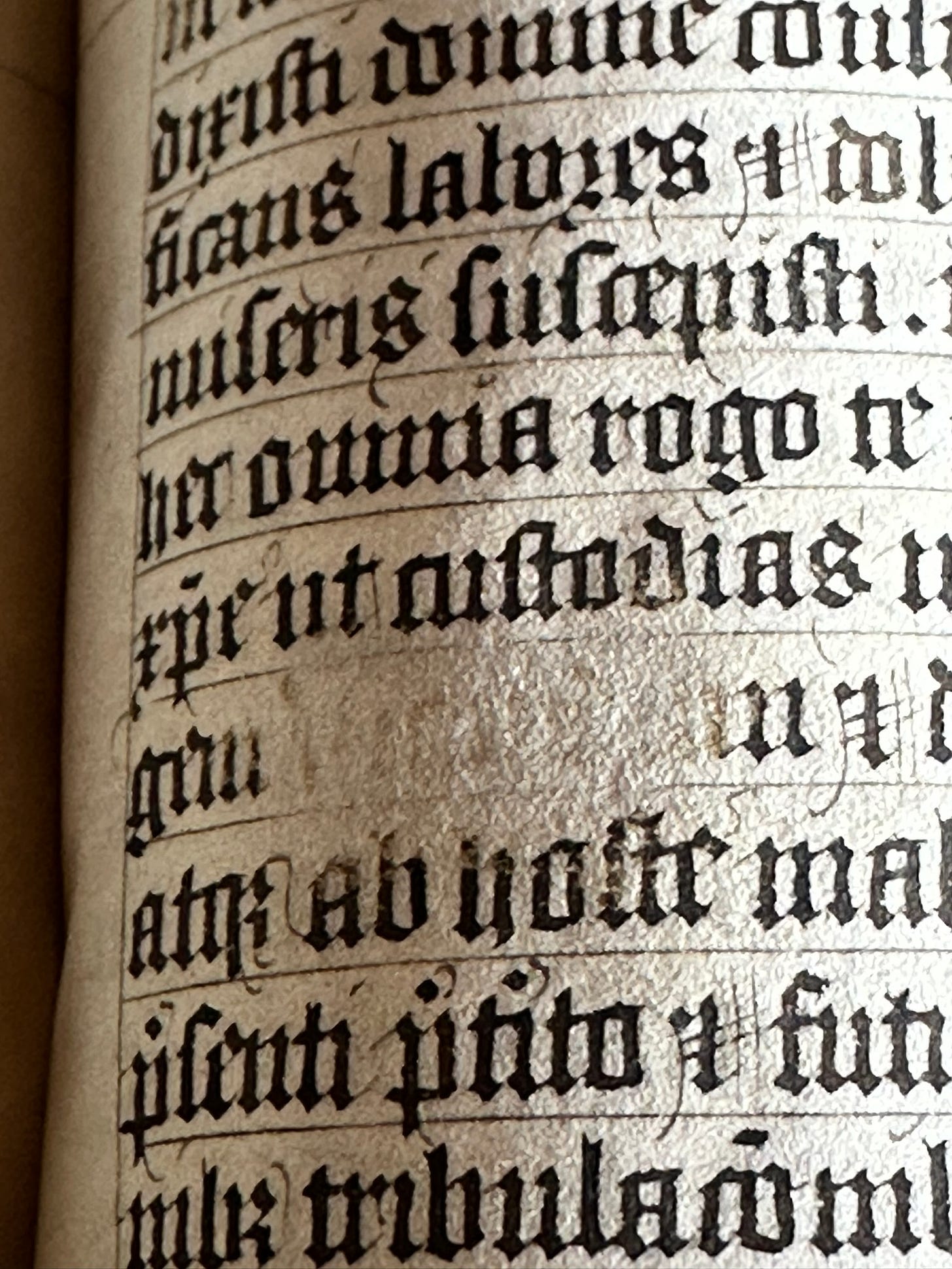

Richard’s prayer covers three pages and offers another window into Richard’s life, this time by focussing on his relationship with God. Once more, the reconstruction will deliver the passage in English rather than the Latin in which it is written so that it can be understood. The important part is the pronunciation of the language and being able to hear an authentic voice of King Richard III speaking words that were both familiar and deeply personal. I was shocked to see that in the prayer, to points at which Richard’s name appeared had been scraped away, like medieval Tipp-Ex. A later owner had deleted Richard’s name from his own prayer, though they’ve left intact the entry of his birthday in the calendar. It was surprising, and quite arresting to see.

The third piece is from a letter Richard wrote to his mother, Cecily Neville, in the aftermath of the death of his only legitimate son Edward of Middleham. In the midst of the political crisis caused by the loss of the Prince of Wales, Richard and his wife Anne are sunk into personal despair at the death of their son. Richard writes to his mother seeking solace and support. It’s a deeply touching moment. A son, devastated by a personal loss that was tragic on several levels, wants his mom. Unlike the other two pieces, this is a letter written in English in Richard’s own hand. We can add to the relationships explored by the project between Richard and his son, and Richard and his faith, that between a son and his mother, ensnared by grief.

The Voice for Richard Project’s recreation of the voice and digital avatar is now on YouTube for everyone to see. I’ve seen loads of incredibly positive feedback recognising the in-depth research and the decade of hard work that has gone into what you can watch. I’ve also seen questions being raised – which is a polite way of saying some keyboard warriors on social media think they know better than professors who have dedicated their lives to their specialities. The accent is wrong, the pronunciation is wrong, the words are wrong. There are a few key points to raise in response.

OP is not a precise science, and no one has claimed it is. It tries to get as close as possible to the way words were said at specific moments in time. David Crystal is a leading expert in his field. He will freely concede that OP cannot account for precise tone, pace, and idiosyncrasies of individuals that are impossible to know. It is as close as it is possible to get, and I’ll take Professor Crystal’s assessment of its veracity over Angry Joe on the internet any day.

I’ve seen it suggested that Richard would have spoken French, not English, or at least would have had a strong French accent. He wouldn’t. French, like Latin, remained a language of business for centuries after the Norman Conquest, but in the early fifteenth century, Henry V closed that particular book by making English the language of government. French lingered, and Richard would almost certainly have spoken French, but as a second language. His first was English. He’d have spoken Old English, Chaucer’s language, other confidently proclaim. He wouldn’t. The Great Vowel Shift happened from the early fifteenth century. English changed radically and quickly. The pronunciation that appears in the reconstruction is accurate.

Others insist Richard would have had an upper-class accent. I asked David about this specifically for an episode of Gone Medieval that you can find here: Gone Medieval | Podfollow. There was no upper-class accent in medieval England. That comes much later. There was some regional changes in accent, but not class-based ones. David Crystal points out that most people who listen to OP from late medieval England will think it sounds, at least in part, like where they are from, because it is an ancestor of modern English, Scottish, Irish, and even Canadian accents.

As a rule, I’d say if you’re attacking the results of the Project’s work, not only are you attacking something that acknowledges its own limitations and potential weak points, but you’re also arguing against the leading experts in their fields.

As well as the episode of Gone Medieval on the Project’s work, the History Hit documentary is out now as well - the trailer is below. We’ve tried to do justice to the incredible interdisciplinary work of the team, the impact it has on our understanding of history, and what it might mean for heritage interpretation. Richard III was the ideal case study to prove the concept. The question now is who might be next. Who would you like to hear speaking to us from across the centuries?

Matt, brilliant overview of this wonderful project. I really think some people actually think everyone in the upper classes have always spoken as Charles iii does with plums up their noses. They forget that this lot went to lessons to speak as they do, it's not natural and it's just to show off. Henry Tudor probably had a Welsh or part Welsh, part Brittany accent.

French hadn't been the English Court language for some time. In Scotland it was because of their closer connections to France. It wasn't in England.